The Kensington Runestone

In this episode:

- Introduction

- Background

- Let the Runes Speak

- New or old Swedish?

- Numbers and Runes

- The hooked X does not mark the spot

- Kensington Runestone and Archaeology

- Geology of the Kensington Runestone

- River kings without rivers

- Here Come the Templars

- Why and Who?

- Support the Podcast

- Sources, Resources, and Further Reading

Introduction

Welcome to Digging Up Ancient Aliens. This is the podcast where we examine alternative history and ancient alien narratives in popular media. Do these ideas hold water to an archeologist, or are there better explanations out there?

We are now on episode 70, and I am Fredrik, your guide into the world of pseudo-archaeology. This time, we will look at the infamous Kensington Runestone found in the USA and the claims made by Scott Wolter from America Unearthed. Is the stone evidence of templars and Scandinavians in the US? Or is it a creation in modern times?

Remember that you can find sources, resources, and reading suggestions on our website, diggingupancientaliens.com. There you also find contact info if you notice any mistakes or have any suggestions. And if you like the podcast, I would appreciate it if you left one of those fancy five-star reviews I've heard so much about.

Now that we have finished our preparations, let’s dig into the episode.

Background

Much like an irritating rash, the Kensington Runestone keeps returning when you think it's finally gone. It again popped up due to Scott Wolter's talk during the Cosmic Summit 2024 and TikToked about by Jahannah James—another promoter of pseudo-archaeological claims and lost civilizations. If you are not familiar with Scott Wolter, he is a geologist, but today, he may be more known as a TV host for the show America Unearthed. One of the entertainment shows promoting pseudohistorical claims put out by the History Channel. There are conspiracies, templars, the Ark of the Covenant in the US, and aliens.

Scott Wolter has also long been a starch advocate for the authenticity of Kensington Runestone (KRS). Meaning the stone was created by American Vikings or at least Scandinavians hundreds of years before Columbus arrived in the Americas. So, let's once and for all put this matter to rest because the case has been closed for quite some time. But before we get into the nitty gritty about the Kensington runestone, we should maybe talk about what it is, where it was found, and when, and whether it's an important discovery in the first place.

Let me then take you back in time to the year 1898. A man named Olof Öhman, a Swedish immigrant, is working hard to clear Internal Improvement Land he recently took over in rural Solem in Minnesota. Under a treestump, he is supposed to find a stone that he first claims might be an "Indian Calendar," his words, not mine. But the stone was later identified as being written with a runic script. I'll first give you the original language and then the English translation.

8:göter:ok:22:norrmen:po:

opþagelsefarþ:fro

vinlanþ:of:vest:

vi:haþe:läger:veþ:2:skylar:

en:þags:rise:norr:fro:þeno:sten:

vi:var:ok:fiske:en:þagh:

äptir:vi:kom:hem:fan:10:man:röþe:

af:bloþ:og:þeþ:

AVM:

fräelse:af:illu:

har:10:mans:we:hawet:at:se:

äptir:wore:skip:14:dagh:rise:

from:deno:öh:ahr:1362:

"Eight Geats and twenty-two Norwegians on an exploration journey from Vinland to the west.

We had camp by two skerries one day's journey north from this stone. We were [out] to fish one day. After we came home we found ten men red of blood and dead. AVM (Ave Virgo Maria) save us from evil.

We have ten men by the sea to look after our ships, fourteen days' travel from this island. Year 1362.”

A theatrical yet short story. There's exploration, there's death and Christianity. Elements that might help us figure out why the stone was made later. I won't be coy about this; the stone is a hoax. I'll prove this from several angles, and all roads lead to a modern creation.

We should touch on a couple of things before proceeding with Öhmans runestone. It's established that the Vikings were in the Americas before other Europeans. The discovery of L'Anse aux Meadows in the 1970s was a huge deal and did show that the Norse sagas were correct about Vinland. However, this settlement was short-lived, and if you want to hear more about it, I'll have a tour of the site in the app Histourian soon. There's also a study from 2023 by Lísabet Guðmundsdóttir showing that elite families in Greenland imported lumber from America. So, today's discussion isn't about whether the Vikings visited North America because we know that they did. So even if the runestone would be authentic, it would, as Professor Kenneth Feder puts it, "No clichéd rewriting of textbooks would be called for, maybe just a footnote." As we will see, however, the importance of the stone is more prominent as a reflection of modern history.

I also want to point out that many authors make the mistake of connecting this stone with Vikings. By 1362, the Viking age was long gone. Sweden and Norway were well into the Middle Ages regarding art and culture. Iceland and Greenland had also followed these new influences at this point. So we should stop trying to connect the stone with Vikings; if it was real, early Nordic medieval would be a better term for the stone—not Norse or Viking.

Let the Runes Speak

The most significant contributor to the confusion regarding Vikings in Minnesota might be that the message is written in runes. I don't think it's weird that people make this association. Still, the issue is that the runic script is not isolated to the Viking age. In Sweden, runes were used for everyday writing up until the 20th century. People were still using runes when the Indianapolis Motor Speedway was founded, and the Manhattan Bridge was open for traffic.

But runes are not some monolithic writing system that's remained unchanged. No, we have several versions, which can be traced back to different periods. The oldest version of the runes dates back to around 100 CE. The system that developed is known as the Old Fuþark. You might wonder what fuþark means, and it's basically the ABC of the old Germanic writing system. We have found several stones where all the runes in the old Germanic alphabet are written out, and the first six signs are F, U, þ, A, R, and K. The Kylver stone on Gotland in Sweden is the oldest example of a complete alphabet and dates back to around 400 CE. Other examples where we find a complete old futhark on the Vadstena bracteate and the Grumpan bracteate. These are medallions meant to be carried around the neck, a fairly common trinket found during this period in Swedish history.

Kylver runestone Photo: Fredrik Trusohamn

As I mentioned, this writing system evolved, and during 800 CE, the old Fuþark was replaced by the new Fuþark. The critical difference between these systems is that the old version contains 24 runes while the younger contains 16. This is a bit of a paradox since we see new types of sounds in the language, meaning more runes would have been better than fewer. During the 9th century, we see, as expected, a period where runcarvers seemed to be able to handle both the new and old Fuþark. The world's longest runic inscription on stone is found in Rök here in Sweden and is an example where the carver understood both writing systems.

Rök runestone Photo: Fredrik Trusohamn

Almost all rune stones are written in the younger Fuþark. Worth remembering, though, is that the runestones were carved mainly during the 11th century and that nearly a quarter of all known carvings in the world are from Uppland in Sweden. During what we would classify as the Viking Age, the young Fuþark was the primary writing system.

But it would not last; we see yet another change as Sweden, Norway, and Denmark enter the early medieval age. The Latin alphabet became the primary writing system during this time, but the runes are still sticking around. Again, they change, and the runic fuþark is replaced by the runic alphabet. The runes go from 16 back to 24 so they can fill out the complete alphabet that was being introduced. While most literate people in Sweden would prefer using the Latin alphabet, there were locations in Sweden such as Gotland, Dalarna, and Jämtland where runes would stick around for much longer. This runic alphabet was used to write both Latin and Swedish. On a spindle whole found in Jämtland, we can read "pax poranti, salus habenti," which translates to "Pace to the bearer, well-being to the possessor." There's also a shaving kit box with runic inscriptions from 1610 but written in Swedish from the era.

With this short crash course in Swedish runes, it becomes clear that different periods and regions have their own set of runes. So, where do the runes on the Kensington stone fit in? You might not be surprised that the runes used are neither the old nor young Fuþark. I hate to bring bad news, but this completely rules out any Viking involvement.

With the Fuþark ruled out, we're left with a runic alphabet. This gives us a window of 700 years, but of course, we can narrow this gap down to a smaller size. The Kensington runes were, for a long time, a bit of a mystery because no known alphabet we knew about did fit with what we see on the stone. Due to this, this type of runes has been known as Kensington runes. The first real breakthrough to finding where and when the runes were made came when the KRS was on loan and exhibition in Sweden in 2003. For the first time, experts in both Swedish and runes could effortlessly examine the inscription. Quite quickly, they realized that these runes looked like those found on a yoke found in Måndalen. The runes carved into the yoke said, "detta bärträ gorde jag den 10 September 1907 oos" and translated to English, saying, "I made this yoke on September 10 1907." It was made by a man called Perlas Olof Olsson and is the first connection between Sweden and the Kensington Runes. They could also quite early connect it to writings by a woman called Gerda Werf from Älvdalen in the region of Dalarna.

Due to the yoke's 1907 date, it was a bit of a chicken or egg situation at first. Was the farmer inspired by the stone written about in the news, or did Öhman learn the signs from the same source? The origin of the Kensington runes has been a bit of a mystery in general. As I mentioned, there are many versions of runic alphabets. Still, none really match the runes we found on this American piece of stone until a few years ago. From a quite surprising source, a middle school teacher and her students.

In 2019, Anna Björk and her students deciphered runes found in a small Swedish parish called Hassela in the northern province of Hälsingland. While the National Heritage Board of Sweden received documentation of the Hassela runes back in 1980, they received little notice until Björk and her students started studying them. With their project, they could shed new light on the region's history. Anna Björk and the kid's efforts were celebrated, and the Swedish National Heritage Board awarded them with a medal of merit.

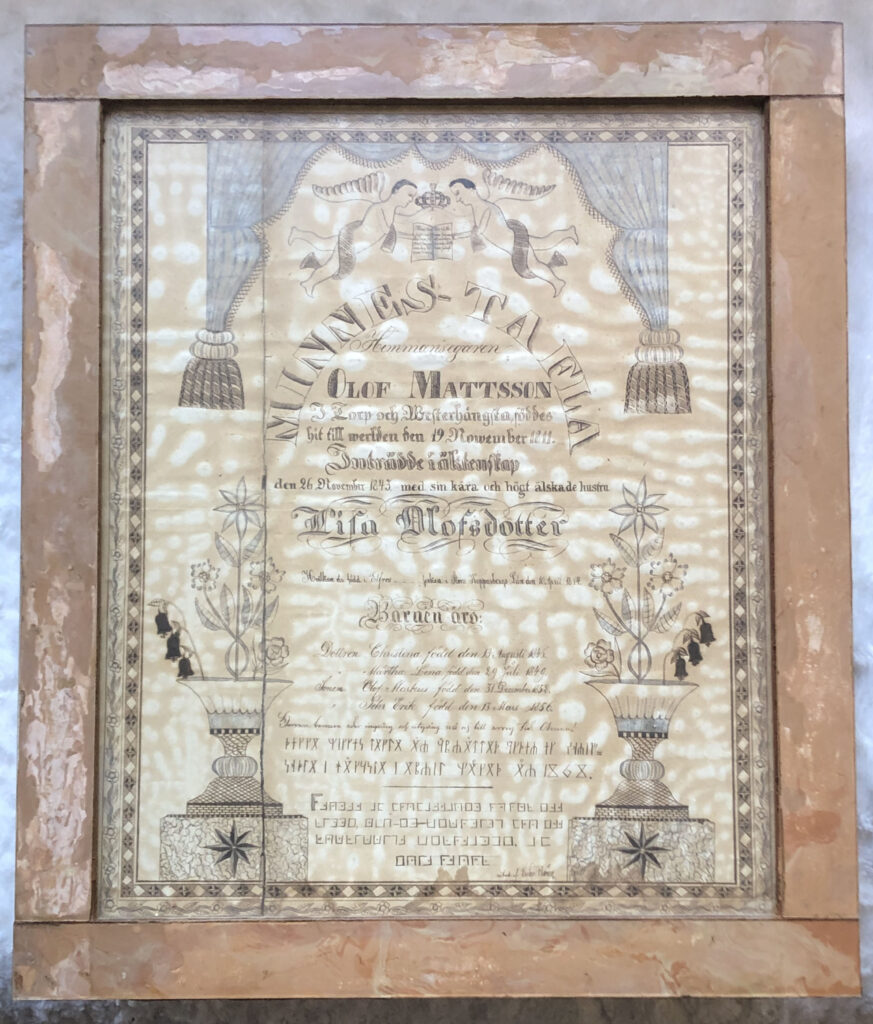

In addition to deciphering the Hassela runes, there was an additional twist. The runes used in this parish were identical to those in Minnesota. Except these predates Öhmans discovery of the stones. With this information, it did not take long for the veil of the rune's origin to fall. Magnus Källström, a runologist and associate professor at the National Heritage Board, did 2022 discover more about where the Kensington and Hassela runes came from. He was tipped off by the regional archive of Medelpad about a memorial plaque with the Hassela runes on it and the date 1868. On it, we can read that this was created to celebrate the wedding between two people in Latin letters. Then we find at the bottom of the plaque a line in Kensington runes saying:

denna minnes tafla är uprättad under en skrifskola i hångsta i april månad år 1868.

This memorial plaque was erected during a writing school in Hångsta in the month of April, in the year 1868.

Further down we find a pigpen cipher where we learn more about the

writer:

Skänkt af författaren såsom ett minne, och en

belöning för ett välvilligt bemötande. af

erik ström

Gifted by the author as a memento and a reward for kind

treatment. by Erik Ström.

Memorial plaque Kensington runes. Foto Magnus Källström (cc-by)

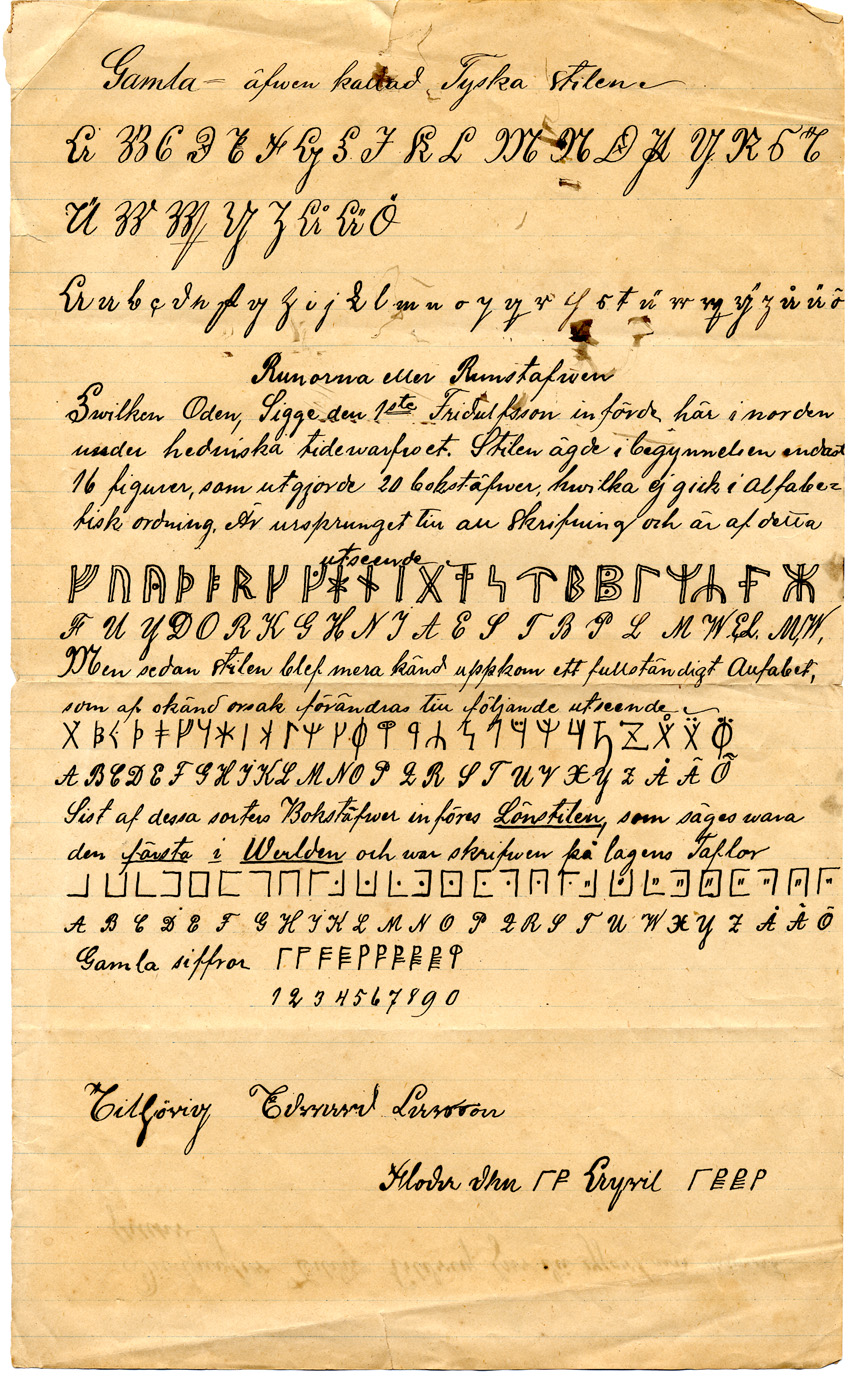

Eric Ström was a writing teacher who specialized in offering classes to workers, household staff, and servants. He was active in the mid-northern part of Sweden. In addition to his teaching, Ström published a booklet featuring several writing systems, including the Hassela runes, which notably include the hooked X found on the Kensington Rune Stone (KRS), as well as a pigpen cipher. Later copies of these runes, such as those found in the practice sheet of Edward Larsson, also contain this exact cipher.

Interestingly, there appears to be both an older and a younger version of Ström's runic alphabet. While Ström may not have been the original creator, the alphabet cannot date back earlier than the 19th century. Evidence suggests that the younger version of Ström's runes was created after 1880. This conclusion is based on a shift in the runic system observed in artifacts like the Haverö staff, the Månsta yoke, and the runes written in Älvdalen.

The most intriguing part is that the runes on the Kensington Rune Stone are written in this younger version of Ström's runic alphabet!

practice sheet of Edward Larsson

Olof Öhman, as you may recall, emigrated to America. He was born in Forsa Parish, located in the Hälsingland province, where the influence of Ström's runic alphabet would have been prevalent. Initially, his surname was Olsson—a typical Swedish name—but he changed it to Öhman upon emigrating to the United States in 1879.

A compelling question arises: Did Olof have any exposure to Ström's runic alphabet? The answer seems to be yes. His first fiancée and cousin, Anna Ersdotter, worked as a vallpiga (shepherdess) in and around Hassela, an area with strong connections to this script. Moreover, the Olsson family owned land in Kolsjön, a region within Hassela.

Though Öhman first emigrated in 1879, he returned to Sweden in 1883, staying for several years before heading back to the U.S. Given the deep connections between Hassela and Ström's runic alphabet, it would almost be surprising if he had not encountered it during this period. He likely spent summers in Hassela while the cattle were grazing, a common practice then.

Some authors have tried to portray Öhman as relatively

uneducated, but this doesn't seem to hold up under scrutiny. He was

literate and seemed interested in history and language. One of the

books Öhman owned is named "The kunskapsrike skolmästaren" or "The well informed schoolmaster." The book aims to give the

reader an understanding of everyday topics. One section deals with

both runes and the medieval language of Sweden. Given his ties to an

area where Ström's script was widely used, it's difficult to

argue that Öhman wasn't familiar with the types of runes on the

stone.

New or old Swedish?

Let's ignore for a moment that the runes used on the stone were created in the 1800s. Instead, we will ask if the language used on the stone is what we expect to find in Medieval Sweden. Again, the answer is no; the language on the stone is not what we see in letters, runestones, or books in the 1300s. Mats Larsson points out that what we see on the Kensington runestone is a mixture of 1800-Swedish, Norwegian, and English. Something that becomes evident if you are familiar with the Swedish language. The stone sounds more like August Strindberg trying to write a runestone than the early medieval Swedish.

The National State Archive of Sweden has many written communications preserved from just the decade of 1360. Most of these communications are donations or receipts of sales or land transfers, but they can still be used to understand how Swedes spoke and spelled in 1362. On the website, I've added two examples of medieval letters, one from Svealand and one from Götaland, the area where those referred to as Göter came from.

“Allum mannum sum thætta breeff høra æller seæ sænder Rangborgh karlsdotter quædio medh guthi ok Ewerthelika helsa”

“Allum þøm mannum þettæ breeff høræ ok syæ sændyr ioan holmgirson æwærdelekæ helso medh guþi”

A fair point to raise here is that these letters would be written by the upper classes. They might not actually reflect how the average Joe spoke during this time. Another point is that the letters are not written in runes. Luckily, we also have many runic medieval inscriptions that we can use. In the Götaland region, we have 67 inscriptions with a secure medieval date. None have the Kensington or Hassela runes, and none have language similar to that on the KRS.

Promoters of the KRS authenticity, like anthropologist Alice Beck Kehoe, point out that some of the words are found in the old medieval Swedish language. But to get there, they sometimes have to go far outside Sweden to find a connection, like the word "from" on line 12. To find a connection to medieval Swedish, you have to go to a dialect found in the Swedish colony in Estonia on the islands of Nukk and Orm. The source is Dr. Richard Nielsen, an engineer, but Kehoe never cited the publication or book where this claim is made.

Line two provides the best evidence for the KRS being a modern creation. The word "opþagelsefarþ" is not found in early medieval Swedish and would not make sense in this period. Henrik Williams points out that the word seems taken from modern Danish updagelsefærd. There's no medieval version of the word. The closest we get is the word "uptaka" in early medieval Swedish, but the word, in this case, would translate to the act of clearing land.

That the language on the KRS is a mixture of modern languages isn't really something that is debated today among scholars with expertise in early medieval Swedish. To be fair, there are critics of this conclusion. One we mentioned at the beginning of this is the geologist and TV host Scott Wolter, who is maybe one of the most active promoters of the stone's authenticity.

The hooked X does not mark the spot

Now, Wolter claims that linguists and runologists are wrong about the stone's language and that it's indeed a 14th-century creation. In his book "The Hooked X," he argues that linguists don't see this because they have not realized the stone is written in Gotlandic. According to Wolter, this misidentification is due to the lack of research on the Gotlandic runestones. This rather bold statement ignores the work that's been done so far, such as Thorgunn Snædal's excellent dissertation on the Gotlandic language and evolution from 2002. The last part of the facsimiles covering the Gotlandic runestones was published with their preliminary findings in 2004 (not 2009, as Wolter claims). These articles also contain previous publications of these stones and inscriptions.

Wolters's argument here is somewhat flighty. The stone gives us the origin of the people mentioned, Göter and Norwegians. Göter, not Goths, are what the people from Götaland on mainland Sweden were called. Gutar is what the people of the island of Gotland are and would have been referred to. Wolter also ignores this in his book and instead relies on cherry-picking data that fits his conclusion that the language is Gothlandic.

Professor Henrik Williams from Uppsala University summarizes why Wolter is incorrect in a 2012 article. The typical medieval Gotlandic S rune is missing from the KRS but is very common in Gotlandic inscriptions. It's strange that such a typical rune is not found on the stone. Williams also points out that Gotland kept its diphthongs for a very long time and found them in written materials on the island. Again, this is something that is missing, along with the Gotlandic case endings on the KRS. So the word for a ship on the KRS should be "skipum" and not only "skip."

Wolter also points out that modern Gotlandic dialects often switch the a at the end of a word to e. For example, gone or "borta" in Swedish is pronounced "borte" in Gotland. On the KRS, we find the word fiske. Still, medieval Gotlandic runestones seem to keep the a. Williams uses stone G 39 as an example. On top of that, we also have G 255, G 240, G 393, and so on. Then there's the issue: On Gotland, the word stone is written as "stain," but on the KRS, it's written as "sten."

With all this in mind, the argument that the author of the KRS

is from 14th-century Gotland is quite obliterated. What's left is the

dotted R, as Wolter calls them, but if you want to look this up,

please search for stung runes. On KRS, we do seem to find stung R's.

While their use on Gotland is intriguing, their appearance on the KRS

could be explained by reasons other than a Gotlandic connection.

Wolter also claims to have found a stung R on stone

G 282, but here, I have to agree with Thorgunn Snædal that it is a

result from flaking—not an intentional stung.

Numbers and Runes

To sum up our findings so far, the text and the runes used don't match with what we see in 14th-century Sweden. So, the case for this being an authentic medieval runic text becomes less convincing as we continue to tally the evidence. Each piece we add to the equation seems to subtract from its authenticity. Now, let's shift our focus to the numbers engraved on the stone. Much like the language, these numerals stand out as anomalies—elements that don't quite fit into the historical equation we're trying to solve.

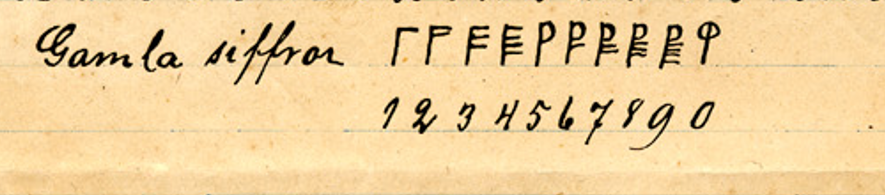

First, the numbers on the stone are written with a sort of pentadic runes. A symbol is used to represent each of the base ten Arabic numerals. One looks like an upper case version of the Greek letter Gamma, so it's a straight line with a vertical line on the top right side. Then, a perpendicular line is added for each number until you reach the number five. At five, the symbol looks like an uppercase P. Then a vertical line is added for each numeral until you reach the ending on 9. A vertical line with a circle on top represents 0.

Pentatic runes

I want to make something extremely clear here: the runic-type numbers found on the KRS are not medieval. There's no medieval text or rune carving using this type of pentadic numbers. The earliest known instance of the use of the KRS numerals is found in the practice sheet of Edvard Larsson in 1885. A sheet that also contains a version of the KRS or Hassela runes. We will later learn that Scott Wolter claims that the KRS was created by Cistercian monks, making these pentadic runes even stranger. Would a Cistercian monk not prefer using the Cistercian numeral system?

So, how did you write numbers in Sweden during the early Middle Ages? Well, as Marit Åhlen points out, with quite a bit of effort. Numbers were written out in almost all cases if Latin numerals were not used. So, if you would like to write that something happened in the year 1350, like on the medieval Gotlandic runestone G 293, it was quite a mouthful. The author wrote the year on the stone as "ett tusen år och tre hundra år och femtio år"/"one thousand years, and three hundred years and fifty years." We see the same practice in mainland Sweden in Sm 114 and VG 210. It's almost as if the carver were paid by the rune. The same goes for the other number on G 293 referring to the birth of Biblical Adam, which is 5201 years before the birth of Christ. Again, the numbers are written out. An exception would be in mainland Sweden on stone DR 366, where Latin Numerals were used.

The same goes for the longest-runic text, Codex Runicus. This is a set of laws from Scania written on vellum with runes around 1300 CE. The most common practice during this time was simply to write out the numbers. Looking back to the Viking age, we find the same practice of writing numerals as text. We still see this practice in the Swedish medieval letters from this period. The only difference is that Latin numerals are a bit more common, but if the Latin numbers aren't used, then the year, amount of money, etc is written out. What we learn here is that if you find yourself back in time working as a scribe, make sure to charge per letter.

With that said, there are cases where runes were used to symbolize numbers in a way. These can be found in the Scandinavian version of the Easter Table, a computation method developed in the Catholic Church to know when Easter was supposed to be celebrated. But also keep track of other celebrations or events you must participate in during the year. So, it's a sort of calendar where the runes are used as arbitrary symbols, not really numbers in that sense. The majority of these types of Perpetual calendars in Sweden are wooden staffs. An alternative version can also be found in a table format often referred to in Sweden as an Easter Table with 19 columns and 28 rows. The earliest known versions of the runic calendars are from the 14th century. However, the vast majority of the almanacs we have preserved are from the 1500s and later.

Runic calendar staff Photo: Fredrik Trusohamn

The staff consists of golden numbers, in this case, the younger futhark with three runes invented for this computation device, representing the 19-year moon cycle. It takes about 19 years for the new moon to appear on the same day again. Then, the first seven runes are repeated 52 times to represent the weeks of the year. The crux here is that to use the runestaf or the Easter Table, you must know the Golden Year and the Dominical (or Sunday) letter. If you have these two, you can calculate when Easter should occur. The upside with the table computation is that you can refer to a year within the Easter Table using The Golden Year and the Sunday letter. Another bonus is that this chart covers 532 years, allowing people to refer to a year between 1140 and 1671 covered by this version.

We have a few examples of medieval rune inscriptions where the texts indeed refer to the Easter Tablet. For example, stone G 171 commemorates a church fire in Hejde. In the last line, we can read, "Then H was the Sunday[-stave] and S the prime-stave in the thirteenth row." If we go to the Easter Table and look for the S rune in the 13th column on the line with a H rune, we can learn the year of the fire. 1492 was the year when the flames were destroying parts of the building. Another example of the use of the Easter Table is on G 78, which tells us when a house remodeling was completed; in this case, it was "And then H was the Sunday[-stave] and K … in the thirteenth row." If we look at our chart, we can see that the kitchen renovation was completed in 1478. Every reference to the Easter Table follows this formula: we get the Sunday letter, the prime (or golden) number, and then what column to ensure we get the correct year.

In "The Hooked X," Wolter claims that there are secret codes hidden on the KRS. One is supposedly a repetition of the year 1362. Wolter mentions that by using the U-rune to the left side in line 9 with the L rune on line 4 (except it's on line 3) combined with the pentadic rune 8, we get the year 1362 on the Easter Table. One of Wolters' claims regarding KRS is that it was a land claim. So, the authors feared that someone would alter the year of the claim by changing the pentadic numeral, moving the date of the claim to another century. A huge flaw, as you might see, is that pentadic runes where not used. Also, it is much harder to change a date that’s written out in text, and if you add the reference to the easter table, it would be basically impossible to change it without destroying the stone.

To support this idea of repeated dates in Medieval Sweden, and especially Gotland Wolter, refers to two stones with the designation G 99 and G 100. The unfortunate reality here is that it's only G 99 that has dual dates. First as "fourteen hundred years and one year less than fifty years" and then "in that year K was the prime-stave and R the Sunday[-stave] in the {eleventh} row." In fact, G 99 is the only stone we have with a repetition of the year. Note here that the carver uses the same formula we see on every other inscription we have. You can also check my work on this since the Swedish National Heritage Board offers a searchable service of all known inscriptions found to date.

Another issue with Wolters's claim is the use of the version of the KRS U-rune. All runestones on Gotland use the U-rune found in the futhark. So it would be quite odd that people trained in a Gotlandic setting would suddenly differ on key runes used during these periods. But as we already covered, the Hassela script is an 1800 creation.

The sum of all this is that the KRS differs significantly from the material found on mainland Sweden and Gotland during the 14th century. The use of Larsson's pentadic runes is another thing that points to a 19th-century creation of the KRS. That we suddenly find a stone that differs so much from all known material is a crucial indicator it was created much later in history. I also want to point out that the book we found in Öhmans possessions also has a section on the old calendars. The Easter Tablet has also been in different prints since at least 1626 when Ole Worm published a copy of this chart. Runic calendars were also commonly used in the area from where Öhman originates. So, both the use and the calculation of dates are well within reason to have been understood and utilized by Olof Öhman or someone cooperating with him.

Kensington Runestone and Archaeology

How about we shift a little and look at the archaeological aspects and findings regarding the stone? Are there any? The answer is an immense no. Professor Feder points out in his book Archaeological Oddities that there isn't a single archaeological trace of Scandinavians in Minnesota during the 1300s. There are no signs of camps, trash, lost items, or anything connected to a Swedish or Norwegian medieval explorer. From an archaeological perspective, we know that this is undoubtedly an archaeological oddity. Finds of the Viking's presence in northern Canada can be found throughout the area where the short-lived settlement was.

The lack of Scandinavian artifacts in the area isn't due to a lack of trying either. Feder mentions excavations that have been done in 1899 and 1964 in the area where the stone was found. Kehoe mentions in her book that further tests and surveys were carried out in 1981 and 2001. You might argue that a small encampment would not appear or be found, but that's not true. Archaeologists do find nomadic temporary encampments all the time. Specifically, there are fire hearths, but there is also a large amount of trash humans have been leaving behind since the dawn of time. If you hike in northern Sweden and know what to look for, you can find these temporary encampments in the landscape today.

It is just not possible that a party of 30 people would come to an area and not leave a single item behind or create a single hearth. Since they took the time to carve a whole slab of stone full of runes, they strongly talk against the ninja-trained Scandinavian. A runestone is not something you bash out during a lunch break. Ten of them even died and must have been buried; even if they had cremated the bodies, archaeological evidence would have been left behind. Some suggest that the dead were Native Americans attacking. Still, even then, it would have been good practice to at least put together a mass grave. As seen in the aftermath of the Battle of Visby on Gotland in 1361.

It might be a bit surprising to learn that Alice Kehoe is a respected anthropologist. Especially since she promotes the idea that the KRS is a genuine 14th-century artifact to this day. As recently as 2016, she proposed the stone as authentic, ignoring the things that don't fit, relying heavily on outdated information or faulty assumptions that we have already covered. Remember that a degree doesn't necessarily protect you against bad ideas if critical thinking is not applied. You might counter here that the stories about Vinland were considered fiction. The key difference here is that Newfoundland turned out to have real artifacts, proving that Vikings visited the area briefly. We're not talking about some century-long occupation; we're talking about a settlement lasting for maybe a few decades at most.

Geology of the Kensington Runestone

Now we come to an area where Scott Wolter could have me beat: the stones' geology. I could add a quip regarding agates here, but I'll refrain. I'm not a geologist, but luckily, I have a couple of geology experts around me.

One part of Wolters' and others' arguments that the stone is authentic is based on the idea that the weathering proves the stone to be of the proper age. However, as geoarchaeologist Dan Fallu told me in a personal communication (twitter), "Weathering has no universal constant rate. It varies with pH, temperature, moisture, energy regime, and mineralogy. Even when you restrict the mineralogy, you still have every other issue." Depending on the environmental conditions, you could try to use soil weathering or clay formations, but this would be highly uncertain on an object already removed from the soil.

I recommend reading Michael Michlovic's 2010 paper and Harold Edwards's 2020 paper for a more in-depth breakdown of the geological claims regarding the Kensington runestone. Anthropologist Andy White wrote a fine post discussing the calcite weathering found in the bottom left corner of the KRS, with input from Edwards.

As for Scott Wolters geological claims about the Kennsington Runestone, they can be summed up in two points.

Wolters first piece of geological evidence compares the pyrite in the KRS and the confirmed hoax called the AVM runestone, a granite gneiss bolder with runes created in 1985. Wolter claims that this comparison shows that the KRS stone must have been made 20 years before Olof Öhman discovered the stone.

Secondly, Scott Wolter also compared biotite found in the KRS with gravestones in Maine. Wolter claims that this comparison shows that the KRS is much older than 200 years due to the weathering of the Mica minerals.

Michlovic raised several concerns regarding this comparison. Other geologists have also determined that the comparison between different rocks is questionable. I even raised an eyebrow regarding this statement. A tombstone in coastal Maine would have quite a different weather and climate than Minnesota in the central US. Why Wolter chose this comparison is unclear. Wolter also uses a minimal sample size on top of all this. In his first comparison, we have one stone of a different type. In the second, he bases his analysis on only three stones. It might be interesting if the tests were based on more slabs and within the same environment. A cause for concern here, however, is that nobody else seems to use this method of dating carvings on stone. It would be amazing to have a way of creating an absolute dating of a carved object in stone. The lack of people pursuing this method might indicate that it does not work as hoped.

River kings without rivers

Another glaring issue with the stone is its location. We learned on the stone that the medieval explorers were 14 days from the coast. But Solem in Douglas County, where the rock was found, is very far from any coast. When Öhman supposedly found the KRS, ships could take the Erie Canal to travel between the Atlantic and the Great Lakes. But this route definitely didn't exist in the 14th century. This means the explorers would have had to push the ships over land for quite a bit or travel solely on foot, a journey definitely more than 14 days. Both operations would have been an undertaking that would have left evidence of their visit. As shown in Europe along the river tradeways, the Vikings operated in the 11th century. So, while the text makes sense in the 19th century, this would not have been the case in the 14th.

Here Come the Templars

But why was the Kensington Runestone created? Let's deal with the more imaginative version first, and then I'll get to the more grounded version. According to Richard Nielsen and Scott Wolter, the Kensington Runestone was created as part of a land claim but, most importantly, by the Templars. Yes, those Templars and, of course, the holy Grail seem to be involved.

Do you remember when I mentioned a hidden code when discussing the numerals? Well, according to Wolter's 2009 book, there is another. By using a microscope, Wolter claims to have seen hidden punchmarks and strokes on certain characters. You can get the following sentence by adding these characters together, according to Richard Nielsen.

Grail; these 10 (men have) Wisdom, (the) 10 (men are with) holy spirit.

The issue with this supposed hidden code is that it builds on Nielsens and Wolters assumptions, attempted translations and subjective symbolism. Could there be a hidden message on the stone? Sure, why not? But this sentence does not prove that the stone is from the 14th century. I looked at a recent high-resolution 3D scan of the stone and could not see these markings. Maybe they are there, perhaps they aren't. Scott is welcome to publish more details about them.

Wolter is trying to present the idea that the Knights Templars went to the US, maybe to hide the Grail or Jesus' bloodline, and have since acted as the man behind the curtain. But how does the island of Gotland fit in? According to Wolters, the Templars had a base there—or at least a connection through the Cistercian Monastery operating on the island. In "The Hooked X," Wolter speculates that a Cistercian monk from Gotland created the KRS.

You might wonder why the Cistercians and Templars are connected to the grail idea. It all goes back to Arthurian legends, especially the work Prose Lancelot. In "Queste del Saint Graal," we get the beginnings of the legends about the Holy Grail. This particular story seems to have been influenced by Cistercian ideals and values that would later influence the Templars. For a more in-depth exploration of this, I recommend reading Karen Pratt’s and Marco Nievergelt's articles on the topic. Something interesting here to note is that according to Stephen Knight, the rise of Arthurian romance works can be connected to a decline in the population's enthusiasm regarding the Crusades. So, in a sense, the legends about the Grail could be viewed as a propaganda tool to promote the Crusades.

It might also be good to mention that Bernard of Clairvaux, the founder of the Cistercians, was a driving force behind the Second Crusade and a co-founder of the Knights Templar order. While Bernard was involved in creating these two orders, it's worth pointing out that they were completely separate orders. Wolter, however, seems to use them interchangeably throughout his book.

The Cistercians indeed had a large Monastery in Roma on Gotland. However, the order had several monasteries in Sweden with stronger ties to both Clairvaux and the mother cloister. Sure, the monks in Roma would acquire large pieces of land later and, through money, grow in importance. As far as we know, the monks in Roma never went to America or seemed to be hiding any grails.

Angel with a concecration cross by it's feets Photo: Fredrik Trusohamn

To support his claim that the Templars and Cistercians controlled the religious life on Gotland, Wolter claims that the churches have Templar Crosses in them. The issue with that claim is that Wolter has confused the Templar Cross with a Consecration Cross. These can often be found in medieval churches, where the bishop spreads holy water during the consecration and consists of a cross within a circle. Wolter also misidentifies a painting of Saint Peter for Bernard of Clairvaux in Lärbro parish church.

A quick lament on my part: Wolter claims that there are six defense towers on Gotland. This is incorrect; there are nine confirmed defense towers and an additional nine, depending on how you define the structure's name within the Swedish language. On top of that, we have records of five more towers but no hard evidence of their existence today.

Wolter also claims that the Teutonic Knights were active in Gotland and part of the KRS expedition. This order is again separate from the Knights Templars, founded by German merchants to support the war in the Holy Land. After the defeat in Acre, the order would later form an independent state in Poland. So, while the order was active in the Baltic area, they were not present in Gotland until 1398, when they invaded the island to protect merchants from pirate activity. The island was under Teutonic control until 1408 when it was returned to the Kalmar Union. So, the orders activity does not fit with Wolter's claims nor the date of 1362 found on the stone.

Why and Who?

So, considering all this, it's hard to make an argument that the stone is from the 14th century. Everything we have found points to a modern date. So who made it? Most likely, Olof Öhman, but he might not have been alone. Two more persons can be connected to Olof Öhman and the stone, defrocked priest Sven Fogelblad and John P Gran. All immigrants from Sweden. In 1967, in an interview later transcribed by the Minnesota Historical Society, Gran's children would admit that their father, together with Öhman and Fogleblad, created the stone. A strange accusation if there was no truth to it.

Worth remembering that the creation of the KRS would not have been long after the National Romance and fascination of the Vikings in Sweden. Societies were created to promote the manly ideas of the brave exploring Vikings. A Viking Revival took place across Europe and the US. Books like Fritiof Saga by the Swedish author Tegner and other books were published and popular. Claims of Vinland really being America and that Scandinavians arrived here before Columbus was theorized by Professor Rasmus B. Anderson and Gustav Storm. The latter writings can be found in Swedish newspapers in the US. The creation would also have coincided with the World Fair in Chicago, celebrating the 400th anniversary of Columbus arriving in America. So, there were a lot of Vikings on a lot of people's minds during this period.

According to the children of John Gran, Öhman and the others seem to have thought it was a great time to create a prank. Maybe even fool those who were more educated.

Archaeologist Carl Feagans makes a connection between the KRS and the Dakota War of 1862. It would have taken place almost next to where Öhman would come to live a few decades later and most likely would have been an event in people's minds still. Feagan writes that the dates' similarity could be a slight nod to the war if the stone is a hoax.

So, in light of all this, the stone has played a more important role in modern history. In a way, the stone is more important as a reflection of American identity and how history is viewed when arriving in a new country. The stone can also be looked at in how it's been displayed in museums and what values and ideas it represents. Is it about the migration of people, or is it representing the founding of the US? So, while it might not be authentic, it can still serve as a way for us to explore history. Even if the events are closer in time.

Support the Podcast

Until then, please spread the word by leaving a positive review on platforms like iTunes, Spotify, or even among your fellow trench dwellers. For more information about me and my podcast, check out diggingupancientaliens.com.

If you want to support the show, head over to patreon.com/diggingupancientaliens, or head on over to archaeologicalpodcastnetwork.com, where you get a ton of bonus content, slack channels, and early ad-free episodes...

Sources, resources, and further reading suggestions

Åhlén, M. (2008). Sifferlös ristning krävde kraft. [online] Språktidningen. Available at: https://spraktidningen.se/artiklar/sifferlos-ristning-kravde-kraft/

Artec 3D. (2024). 3D Model Of The Kensington Runestone. [online] Available at: https://www.artec3d.com/3d-models/kensington-runestone

Beck Kehoe, A. (2005). The Kensington Runestone. Waveland Press.

Beck Kehoe, A. (2016). Traveling Prehistoric Seas. Oxon: Routledge.

Benneth, S., Ferenius, J., Gustavson , H. and Åhlén, M. eds., (1994). Runmärkt. Från brev till klotter. Runorna under medeltiden. Stockholm: Carlsson.

Brate, E. (1922). Sveriges runinskrifter. [online] Stockholm: Natur och Kultur. Available at: https://runeberg.org/runor/.

Colavito, J. (2014). Scott Wolter Lawsuite: Albert H. Petersen vs. Scott Wolter, 05-CX-88-000692 (1989). [online] Jason Colavito. Available at: https://www.jasoncolavito.com/scott-wolter-lawsuit.html

Edwards, H. (2020). The Kensington Runestone: Geological Evidence of a Hoax. The Minnesota Archaeologist, [online] 77, pp.6–40. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/45218145/The_Kensington_Runestone_Geological_Evidence_of_a_Hoax.

Feagans, C. (2023). The Kensington Rune Stone Hoax - Archaeology Review. [online] Archaeology Review. Available at: https://ahotcupofjoe.net/2023/07/the-kensington-rune-stone-hoax/.

Feder, K.L. (2019). Archaeological oddities : a field guide to forty claims of lost civilizations, ancient visitors, and other strange sites in North America. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

Feder, K.L. (2020). Frauds, myths, and mysteries : science and pseudoscience in archaeology. 10th ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Guðmundsdóttir, L. (2023). Timber imports to Norse Greenland: lifeline or luxury? Antiquity, 97(392), pp.454–471. doi:https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2023.13.

Gustavson, H. and Snædal, T. (2017). Gotlands runinskrifter 3. [online] Riksantikvarieämbetet. Available at: https://www.raa.se/kulturarv/runor-och-runstenar/digitala-sveriges-runinskrifter/gotlands-runinskrifter-3/

Hagland, J.R. (2014). Etterreformatoriske Runer Og Kvardagsleg Skriftpraksis På 1800-talet. In: A.-C. Edlund, L.-E. Edlund and S. Haugen, eds., Vernacular Literacies - Past, Present and Future. [online] Umeå: Institutionen för språkstudier, Umeå universitet, pp.155–164. Available at: https://umu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A736804&dswid=-2044.

Hamp, C. (2024). D Skansvakten 1977;16 - Dalarna Älvdalen. [online] Christerhamp.se. Available at: https://www.christerhamp.se/runor/gamla/d/dskansvakten1977.html

Hjorthén, A. (2010). Historia skriven i sten? Bruket av Kensingtonstenen som historiekultur i svenska och amerikanska utställningsrum. [Master Thesis] Available at: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:320121/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

Hjorthén, A. (2021). Transatlantic Monuments: On Memories and Ethics of Settler Histories. American Studies in Scandinavia, 53(1), pp.95–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.22439/asca.v53i1.6221.

Källström, M. (2019a). En kyrkbrand och en märklig h-runa - K-blogg - Riksantikvarieämbetets blogg. [online] K-blogg - Riksantikvarieämbetets blogg. Available at: https://k-blogg.se/2019/04/28/en-kyrkbrand-och-en-marklig-h-runa/

Källström, M. (2019b). Fler Kensingtonrunor i Hassela - K-blogg - Riksantikvarieämbetets blogg. [online] K-blogg - Riksantikvarieämbetets blogg. Available at: https://k-blogg.se/2019/05/30/fler-kensingtonrunor-i-hassela/

Källström, M. (2019c). Kensingtonrunor i Hälsingland - K-blogg - Riksantikvarieämbetets blogg. [online] K-blogg - Riksantikvarieämbetets blogg. Available at: https://k-blogg.se/2019/03/09/kensingtonrunor-i-halsingland/

Källström, M. (2020). The Haverö runes – the key to the mystery of the Kensington Stone? [online] Riksantikvarieämbetet. Available at: https://www.raa.se/in-english/the-havero-runes-the-key-to-the-mystery-of-the-kensington-stone/

Källström, M. (2022). Kensingtonrunorna Kom Från Timrå! [online] K-blogg - Riksantikvarieämbetets Blogg. Available at: https://k-blogg.se/2022/12/11/kensingtonrunorna-kom-fran-timra/

Källström, M. (2024). Till frågan om Kensingtonrunornas ursprung och spridning. Futhark International Journal of Runic Studies, 13, pp.87–113. doi:https://doi.org/10.33063/diva-525135.

Kitzler Åhfeldt, L. and Källström, M. eds., (2022). Det Öppna Och Det fördolda: Runor I Olika Sociala Miljöer Från Senvikingatid Till Efterreformatorisk tid. Visby: Riksantikvarieämbetet.

Knight, S. (1994). From Jerusalem to Camelot: King Arthur and the Crusades. Medieval Codicology, Iconography, Literature and Translation, pp.223–232. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004622722_026.

Krueger, D.M. (2015). Myths of the Rune Stone. University of Minnesota Press.

Lagman, S. (1990). De stungna runorna. [online] Uppsala: Instititionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet. Available at: https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A958405&dswid=2699.

Larsson, M.G. (2012). Kensington 1898 - Runfyndet Som Gäckade världen. Stockholm: Atlantis.

Larsson, M.G. (2020). Gästblogg: Kensingtonrunorna Allt Närmare Olof Öhman - K-blogg - Riksantikvarieämbetets Blogg. [online] K-blogg - Riksantikvarieämbetets Blogg. Available at: https://k-blogg.se/2020/07/21/gastblogg-kensingtonrunorna-allt-narmare-olof-ohman/

Larsson, M.G. (2021). Gästblogg: Nya Upptäckter Leder Kensingtonrunorna Ännu Närmare Olof Öhman - K-blogg - Riksantikvarieämbetets Blogg. [online] K-blogg - Riksantikvarieämbetets blogg. Available at: https://k-blogg.se/2021/08/03/gastblogg-nya-upptackter-leder-kensingtonrunorna-narmare-olof-ohman/

Liljegren, J.G. (1832). Run-lära. [online] Stockholm: Norstedt & Söner. Available at: https://litteraturbanken.se/f%C3%B6rfattare/LiljegrenJG/titlar/RunL%C3%A4ra/sida/203/faksimil?storlek=5.

MHS Collections: The Case of the Gran Tapes: Further Evidence on the Rune Stone Riddle. (1976). Minnesota History, [online] 45(4), pp.152–56. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20178443.

Michlovic, M.G. (2010). Geology and the Age of the Kensington. Minnesota Archaeologist, [online] 69, pp.139–160. Available at: https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=477106a1-39e8-3fd5-824b-a5e980460443.

Nielsen, R. and Wolter, S. (2006). The Kensington Rune Stone. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform.

Nievergelt, M. (2007). The inward crusade: the apocalypse of the Queste del Saint Graal. Neophilologus, 92(1), pp.1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11061-007-9050-3.

Nordberg, T. (2013). Jokers, Liars, and Dumb Clucks: The Curious Case of the Kensington Rune Stone. Kindle.

Ohman, E. (1949). Edward Ohman Interview, 1949. [online] Available at: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/mnoralhistories/88/.

Pratt, K. (1995). The Cistercians and the Queste del Saint Graal. Reading Medieval Studies, [online] XX, pp.69–96. Available at: https://centaur.reading.ac.uk/84625/.

Riksantikvarieämbetet (2020). How the Runes went from Hassela to Minnesota. [online] RAÄ. Available at: https://www.raa.se/in-english/how-the-runes-went-from-hassela-to-minnesota/

Rosander, C. (1882). Den kunskapsrike skolmästaren, eller hufvudgrunderna uti de för ett borgerligt samfundslif nödigaste vetenskaper. [online] Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag. Available at: https://runeberg.org/rcskol3/.

Snædal, T. (2002). Medan Världen Vakar : Studier I De Gotländska Runinskrifternas Språk Och Kronologi. [online] Available at: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-1951.

White, A. (2016). Calcite Weathering and the Age of the Kensington Rune Stone Inscription (Lightning Post). [online] Andy White Anthropology. Available at: https://www.andywhiteanthropology.com/blog/calcite-weathering-and-the-age-of-the-kensington-rune-stone-inscription-lightning-post

Williams, H. (2004). The Kensington Runestone on exhibition in Sweden. Nytt Om Runer : Meldingsblad Om Runeforskning, [online] 19, pp.35–36. Available at: https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:720566/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

Williams, H. (2012). The Kensington Runestone: Fact and Fiction. The Swedish-American Historical Quarterly, [online] 63(1), pp.3–22. Available at: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:543322/FULLTEXT01.pdfMinneapolis.

Wolter, S.F. (2009). The hooked X : key to the secret history of North America. St. Cloud, Minn.: North Star Press Of St. Cloud.

Worm, O. (1643). Fasti Danici. [online] Available at: https://books.google.se/books?id=uv5XAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.